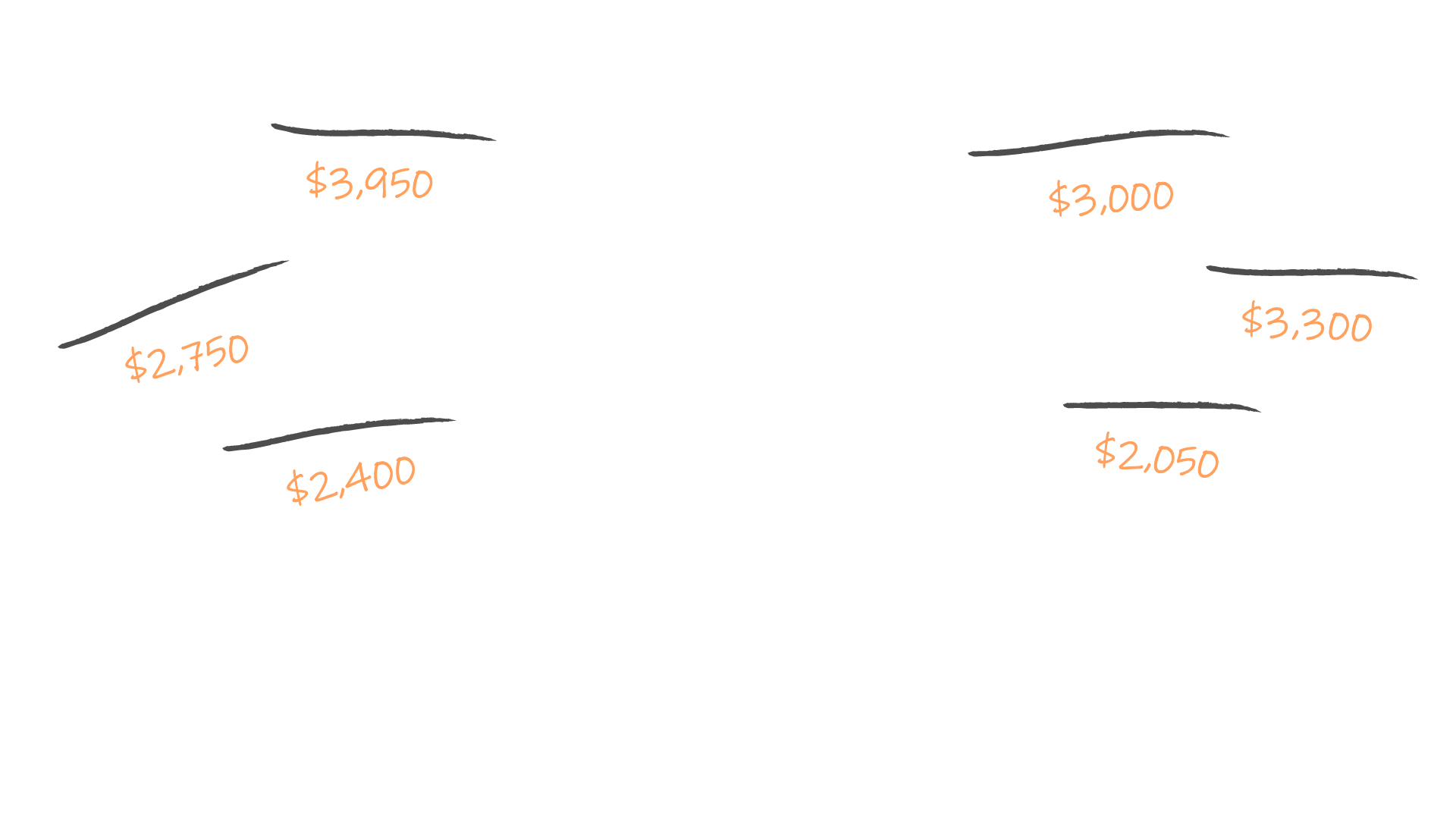

In Allston, a quarter of all apartments were bid up from their initial list price. Data show that the neighborhood’s popularity among university students may be partially to blame for the high rate of rent bidding.

There is a consistent pattern across Boston ZIP codes: Areas with more students also tend to have higher rates of rent bidding.

Undergraduate students are a big contributor to that pattern. Although most of them live on campus or in university-provided housing, there were still 18,500 undergraduate students who competed for rental market housing in 2022.

That pattern is particularly strong when it comes to graduate students, who are responsible for 37% of the rent bidding variance in a given ZIP code. Generally speaking, a ZIP code’s rate of rent bidding increases by 1% for every 275 graduate students living there.

While undergraduate enrollment has remained relatively flat over the last 10 years, the number of graduate students across Boston has risen 20% just since 2020, according to the City of Boston.

Only 10% of graduate students live on campus or in university-provided housing, making rising rates of enrollment a concern in a tight housing market.

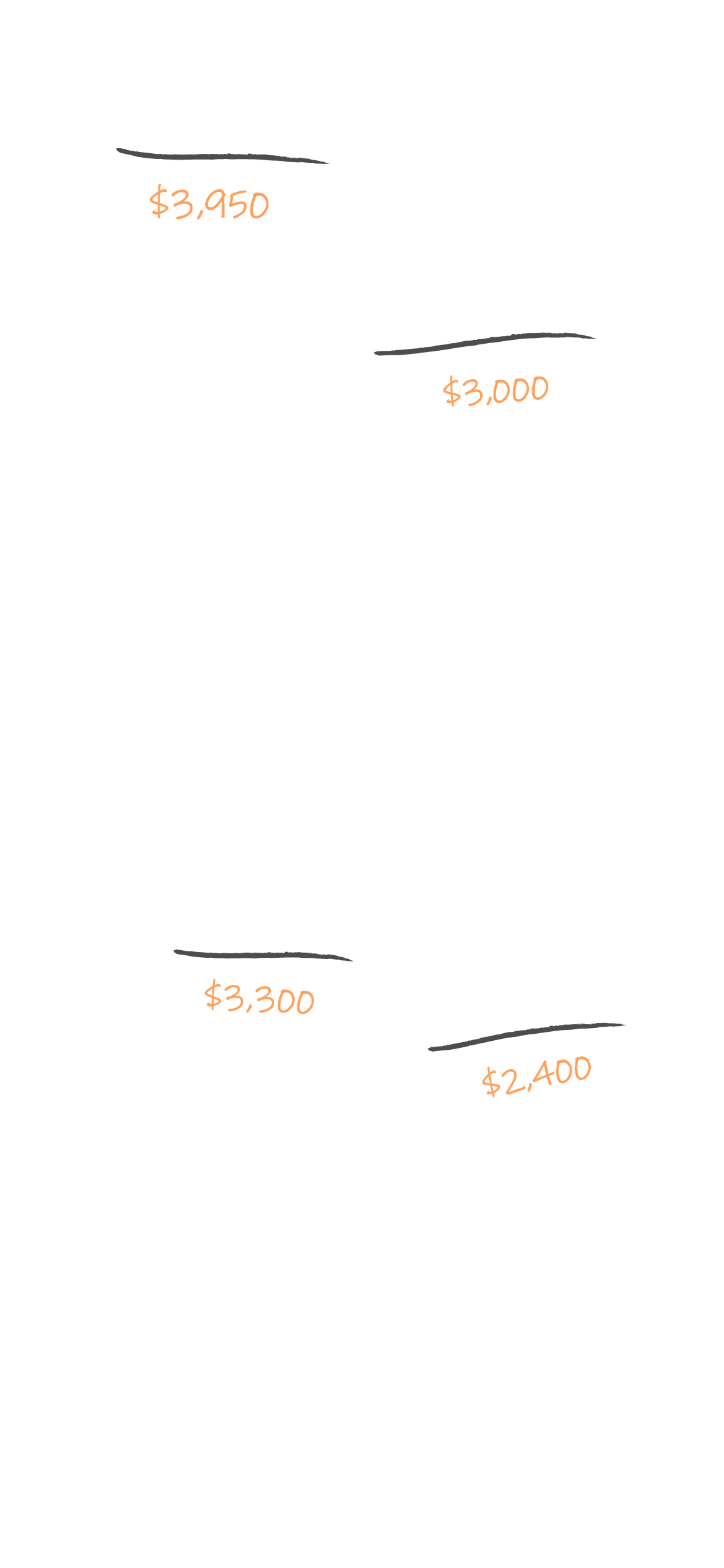

Nearly three-quarters of Boston’s graduate students are concentrated in just five ZIP codes. On average, 17% of rentals went for above the asking price in these neighborhoods — 4% higher than the average rate for the rest of Boston.

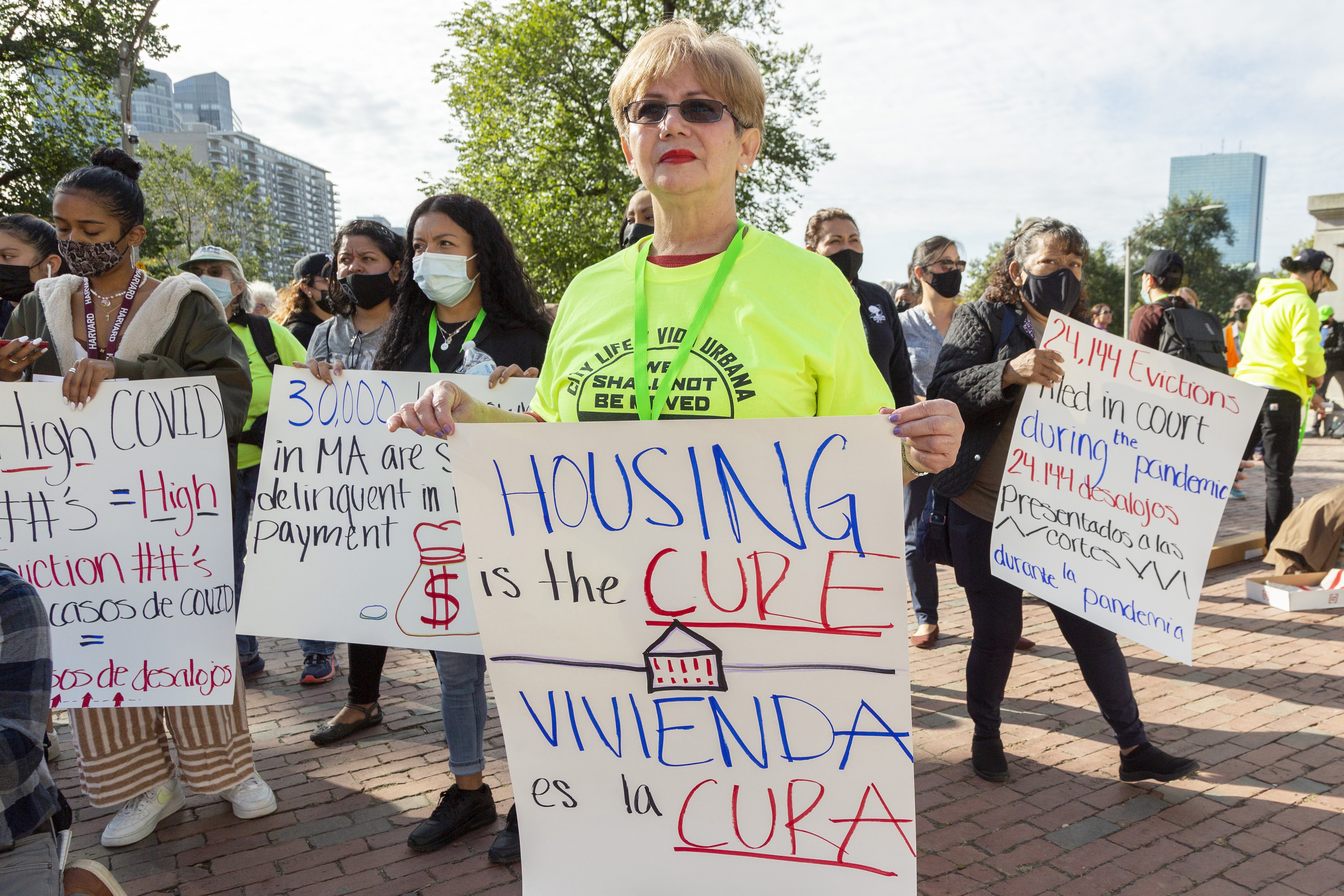

Doucette, a Somerville-based real estate agent, said all of her clients who participated in bidding wars this year were students, usually at the graduate level. “I don't really see bidding wars amongst working people. It's mostly this Sept. 1st student rush,” she said. “It's just very competitive. And it seems like they're willing to pay whatever it takes just to get into the apartment.”